By Giulia Piceni. Cover photo by Naufal Farras.

Writer, editor, curator, and cultural provocateur Gianluigi Ricuperati is known for crossing boundaries between literature, philosophy, and contemporary culture. A restless intellectual presence on both the Italian and international scenes, his work challenges conventional categories—blending the analytical with the poetic, the visionary with the precise. In this long-form conversation, Ricuperati explores the language of intelligence, the urgency of fiction as a moral and imaginative force, and the poetic density of text in an increasingly fragmented world. As algorithms flatten meaning and attention fractures, he defends the slow, vital labor of thinking, reading, and writing as a radical, almost rebellious act. He has published essays and novels with various publishers and contributes regularly to outlets including La Repubblica, Abitare, and Il Sole 24 Ore.

Language as Transformative Matter

You work as a curator, novelist and journalist. Text is a central component in your practice. Was there a formative moment when you first understood the transformative power of language not just as a tool, but as a material?

It was in my late teenage years, around nineteen years old, when I read for the first time the beautiful text that Roland Barthes wrote about Cy Twombly. It was just a single text. Actually, there were two. The second one is a text by Italo Calvino on Domenico Gnoli. You have to consider that for me those two names were completely unknown. I had always been interested in literature and in the arts, but I didn’t come from an art-related family, so these two names were like nothing to me. But that’s exactly the transformative power of language, when it sparkles an interest out of nothing, when it creates something out of nothing. I think that maybe this is because it replies to the transformative power of matter and the beginning of the universe. So sometimes physicists or great scientists are questioning what was before the Big Bang, and nobody exactly knows. It’s also because it’s difficult to imagine, to conceive the idea of pure nothingness. And maybe that’s not the right idea, but what is true is that that power, that language, are energies that transform.

Galaxies, Geometry and Meaning

And maybe it’s at the base of the universe. At least our universe (of the ones that believe in words).

I believe in replicating things and in not replicating things. I believe in the idea that you find in the smallest examples the traces of the bigger schemes. Sometimes when you push your eyelids with your finger and your eyes are closed, you see shapes that are very much similar to the photos of the universe. I think that the same goes for small leaves that have some geometrical forms, and obviously the laws of physics are like governing, like the music is governing everything and they work for very small objects. And so I just heard a beautiful remark from the great Richard Feynman, the great physicist. He, a Nobel Prize winner, said this incredible thing. Obviously, you feel kind of humbled when you think about the quantity of galaxies that there are in the universe. But also, if you want to rebalance things, you can think of the other way around. You can think of yourself, your body, how big it is if confronted with a single atom. And that balance sticks.

Text as Object and Language as Fabric

Let’s move from one universe to the one you’ve created: Nova Express, the magazine you curate. You approach text both as content and as an object. What draws you to this hybrid format, and how does it differ from more traditional editorial structures?

It’s interesting to note that Nova Express, the title of the magazine, comes from William Burroughs’ novel, an experimental sci-fi work from 1964 or 1965. That says a lot. I’ve always been drawn to the idea of science fiction, of exploring different possibilities of the real. But I’m also deeply interested in the interplay of language, and in the structures within language. I like diving into the fabric of it: that’s really what the novel is about.

And of course, the magazine’s art director and graphic designer is also an artist: Andrea Magnani. The way he approaches text is both semantic—he reads and understands it—and visual. I’m not saying we’re doing visual poetry exactly, because that’s not quite it. But we definitely treat text as part of a kind of… let’s say, cosmic dance on the page. Cosmic Dancer. It’s a beautiful song by T. Rex.

It was in the movie Billy Elliot, I remember it from my childhood.

And by the way, it was covered by Morrissey and David Bowie. The first time I heard the song was through the cover by Morrissey. There’s a beautiful YouTube video dedicated to it. David Bowie was a very close friend of Marc Bolan… he (Marc Bolan) was a visionary genius who unfortunately died too early. He died in a car accident in 1977, the year I was born. But what happened is that I think if he hadn’t died so young, probably his parable wouldn’t be much beyond the so-called glam rock of the ’70s. But this is another story.

When Words Dress Fashion

Agreed, agreed. Returning to the concrete way you work with words, in one of the latest editions of Nova Express there was a word-based campaign by Valentino, using only words to present fashion. What do you think is the role of text nowadays in the fashion industry?

Well, for sure there’s a renewed interest in poetry and there’s a renewed interest in narrative in the fashion arena, and that’s an important thing. The fact that someone like Pierpaolo Piccioli is again the creative director of a big brand like Balenciaga will spark new interest in the fashion crowds as he is a passionate reader of poetry. I mean, what is important is not just creating literary works but also reading: the two things come together. It’s like pleasure: you cannot have pleasure if you don’t give it. The same thing goes with literature. You cannot be a poet or a serious writer if you’re not a serious reader. It’s really the same thing. It’s the same thing but it’s two aspects of the same coin. So you throw the coin in the air and the moment the coin goes up it’s a beautiful moment because you see reading and writing. I think that in fashion this could be a transformative movement because it could give more gravity and more substantiality to the discourse, to the practices of fashion making and ultimately to the products. So I think that the transformative power of language can also be visible in fashion and I think this is the moment where it can happen. And then of course there is AI. Obviously I have nothing against its use. I think it’s very interesting what you can do as a writer, but you cannot simply write a prompt and wait for the machine to do the rest because that’s not the right way to do it. It must be a collaboration, you can also do it without it. I mean: the possibilities are endless. But what is certainly not good is when you read press releases that are clearly written with AI. You can immediately feel it if you have a certain sensitivity for language. You see that… let’s call it that average buzz. Yes, I would call it like this. I wouldn’t call it the death of humanity…

Responsibility, Language, and the Aura of Meaning

It’s a flattening.

Yes, of the unexpected, of everything. Sometimes we forget that humans are made of neural interconnections, but these neural interconnections are placed in a body and these bodies are in relationship with other bodies and they are placed historically. We’re in a line that both goes up and obviously goes also straight, but also goes backwards — so history — and which leads to ethics and responsibilities. For example you cannot sue an artificial robot or an artificial intelligence. So responsibility, body, interaction… All these things are true for language and are true for fashion. Everything is about these things. I mean, you’re not doing it alone, you’re doing it in history. You have the responsibility. And by the way, I really like the idea of describing things as the moment you describe things with words and with images, you create a different aura.

Words That Linger, Between AI and Language

Also, is there a word, a phrase, or a syntactical form that keeps haunting your writing, something that keeps resurfacing? Do you find yourself wanting to avoid it, or do you end up embracing it?

Beautiful question. Obviously, in this case, we should think of an Italian word, because even if I write now also in English, for instance, the use of AI is really interesting to make you polish your English sometimes and to verify the correctness in an average form, which is interesting. So sometimes, obviously, I think about this also… but this is another thing you’re asking me.

Writing the Future: Tense, Responsibility and Fiction

I’m also fighting with that. My conscience is telling me not to use it, but sometimes it comes in handy.

Sometimes it’s useful, and it’s part of everyday life, and everybody uses it. And it’s okay. The thing is, the collaboration should be like this: that this gives you something, and you rewrite it — but you rewrite it in your own way. One thing that I did was go back to writing on a laptop that’s depleted of all these apps, so it’s basically used as a typewriter. This has improved concentration very much, because the one thing we need as humans is focus. And focus is very close, very linked, to breathing in and breathing out. As I said, machines don’t have bodies. I mean, they have bodies like the servers, for a while, but it’s different. But you know, I’m just stealing time. You know, there’s not a specific word that I like, but at this moment, I like the idea — because I’m writing about it — of the use of the future tense in fiction, and in writing in general. In Italian, there is this beautiful tense, which is not just the future “I will do” but the futuro anteriore, the future perfect, which can be translated as “I will have done.” So my answer would be this: the idea of the past of the future. Do you know why? Because the use of the future tense immediately invokes the role of prophecy, which is one of the first ways language was ever used. It’s a religious function. And prophecy is very important in the history of humanity: it’s about knowing what will happen next, but on the other hand, it’s also related to the idea of will. So again, it’s a link between what is under your control and what is above your control between responsibility and destiny. And this is just to say… I like the idea of writing something and I’m actually doing it. Some portions of the text I’m writing, of the novel I’m writing, are entirely written in the future tense. Or much better: the same stories are told in the past tense and then rewritten in the future tense, like you’ve come back to the day before, the moment before the action happened.

Imagine this: you talk about a day trip with your family or with your friends at the lake, and something goes wrong — not terribly wrong, but maybe you have a fight with someone. And so you reflect on it and write about it in your diary. Then you rewrite the diary by going backwards in time and adjusting things in the day so you write a diary in the future. It’s part of the book I’m writing now. It’s some portions that are part of the diaries or, let’s say, autobiographical fragments. It’s not entirely autobiographical, but they are diaries rewritten in the future so that, instead of getting consumed by the sense of shame or the sense of guilt because maybe you’ve done something wrong… And there’s a huge potential in fiction, and also in life, because maybe it helps you come to terms with what has happened. Because there is a certain mystery — I mean, a kind of metaphysical shock — to the fact that something has happened and it’s not manageable anymore. You cannot edit it anymore. You cannot edit the past, while our digital eternal present always allows this continuous, continuous editing of things. So that’s it. I mean, maybe it’s not even a single word.

Writing Across Roles: Novelist, Journalist, Curator

And speaking of your novel, you’re not only a novelist, but also a journalist and a curator. Each of these roles implies a different approach to writing. Do you feel like a different person when you write in each of these contexts? How does your thinking shift between them?

It’s interesting because now that I’m writing a book I have the absolute necessity to write continuously, so at least some hours a day, every day, no matter what. It’s not a matter of the number of hours, but it’s a matter of keeping on the trend. It’s exactly like this: you need to move on every day because you keep on reminding yourself. Writing—especially fiction—is a kind of war, or an act of resistance against its own apparent uselessness. I mean, the world doesn’t need it… until it does. Until it can’t be without it. Take 1984, for example. When Orwell was writing it, the world didn’t need 1984—even though it was a world torn apart by war, with the nuclear bomb having just exploded. Still, he wrote it. No one asked for it. But now, we can’t imagine a world without 1984. That’s what fiction does. And to write it, I think, you have to be a true believer. Because it demands a lot. That’s why it can be so heart-wrenching—and sometimes painful.

From Personal Calling to Teamwork: Writing in a Machine Age

It’s a calling. You can’t control it.

You need to believe in it, and you also need to be surrounded by people who believe in it, just as you always need support. I mean, it’s a heavy situation. On the other hand, journalists have to be completely different. The feedback and response times are very quick, and the position you hold requires a certain degree of skepticism. There’s a necessary detachment, and you have a responsibility—you cannot make things up.

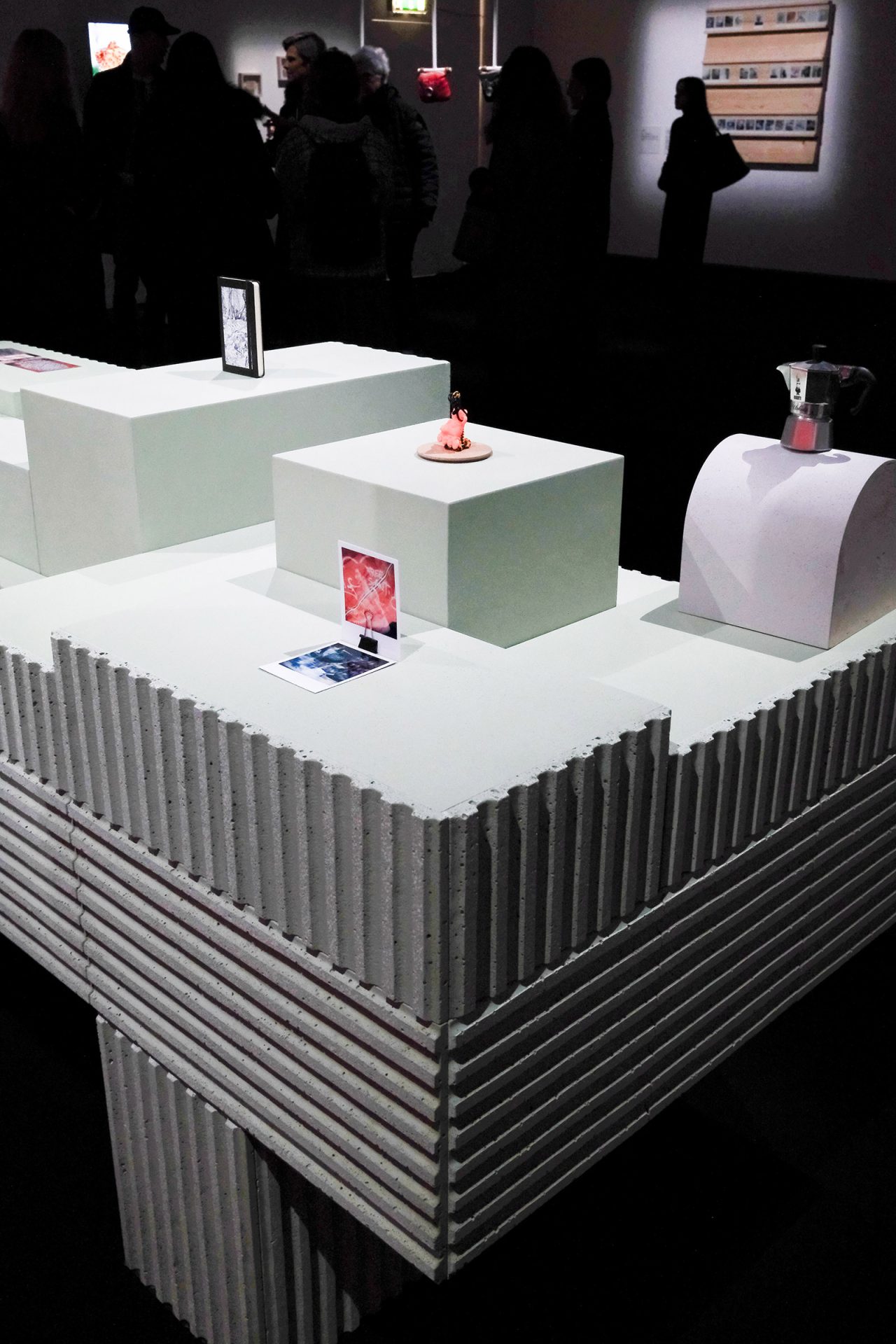

Then there are other forms of writing that are more service-oriented. Right now, I’m curating a project for K-Way, which is a beautiful, intricate, complex, and long-term project I’m involved with on every level, including the words. Since it’s a team effort, sometimes people remind me, “Remember the deadline for those panels we have to put in that room for the exhibition,” because the exhibition moves between different cities, so it’s a lengthy process. “Yes, I have to remember,” I say, but I’m late anyway. Then one of these really kind people—because they know how much I’ve worked on this project—said, “Don’t worry, we wrote it with AI, but we know it’s not great, so maybe you can retouch it.”

So they give it to me, I rewrite it, and sometimes it’s interesting. I sometimes leave a couple of lines that, for some reason, are slightly off but still understandable—a small sign of disruption against the machine’s language standardization.

On Curating, Generosity, and the Power of Language

Yes, that was another key point I wanted to explore about curating. There’s definitely responsibility, but also a sense of generosity. What do you think? Since you mentioned service-oriented texts, isn’t curation today also an act of generosity toward both the material and the audience experiencing it?

It’s a beautiful idea you bring up and I think it’s important. You do need to be generous. I like the ambivalence of it. Yesterday, I was in Siena visiting the Santa Maria della Scala complex, which was formerly a hospital. It’s an extraordinary place, filled with frescoes by great painters from the early Renaissance. And what’s remarkable is that it was used as a hospital right up until the 1990s. Now, it’s a museum, just across from the Duomo. And being there made me think of the semantic ambiguity of the word curare — to care, to heal — and the figure of the curator. More than healing, which is the metaphor everyone leans on today, I’m interested in that expanded scope of curating, which now reaches far beyond just art. For instance, I’m curating an exhibition in September about time, or rather, about time as a machine. And part of curating, of course, is purely logistical. You become a knot among knots. We have twelve works that need to be loaned from various collectors, so you need to speak with galleries, with collectors. You need to be polite, persuasive and convincing. And the way you use language matters enormously in that process.

You become faster if you’re good with words. Of course, you could ask an AI to write a convincing message, but it will always miss something. I like to add a detail that’s a little strange, something that signals a human presence: a phrase or combination that maybe isn’t quite right in English, not commonly used, but still communicative. And that difference makes it feel personal. It gives a sense of who I am. That’s also why I like people who maintain their accent. I’m not fond of the caricature of accents. When you speak English, it’s okay to lean toward a British or American intonation, but not to the point of imitation. You shouldn’t sound like a Texan or an Oxford schoolboy if that’s not where you’re from. In your intonation, in small mistakes, in how you treat vowels… there should be some trace of your mother tongue. Which brings me to something I’ve been thinking about, a concept I’ve only recently developed but haven’t fully pinned down yet: the opposite of a mother tongue might be a daughter tongue or a son tongue. That is, the language you learn as an adult. A language that’s not inherited, but chosen and into which you try to pour yourself, trying to be correct and understood, yes, but also to leave a mark.

On Mistakes, Authenticity, and That 2% of Magic

To maintain the sense of authenticity.

Authenticity, yes. And maybe allowing a few beautiful mistakes to come to the surface. Like those rare, luminous fish that rise from the depths of the sea, maybe just for a second, drawn by curiosity. Like in Finding Nemo, when that strange fish swims upward just to catch a glimpse of the light before sinking back down again. I like to think that when you’re writing or speaking in another language, a small part of your unconscious — maybe just 2% — emerges in that way. The rest, 98%, might be technically correct, polished, functional. But that 2%? That’s where the strange associations live, those combinations of words that carry echoes or translations from your original language. And that 2% is often the most human, the most interesting. It’s a long story, but I like it.

Language as a Form of Intelligence

One last question: We’ve talked a lot about AI, which is unavoidable these days. But do you also rely on other kinds of intelligence? And do you see language itself as a form of intelligence we can consciously use and depend on?

By intelligence as a reference point or guidance, do you mean other kinds of intelligence beyond human and artificial intelligence?

Wild, Intuitive, and Unwritten: Nature’s Intelligence

Yes. Natural, even animal.

It’s a very nice question, very interesting. Well, I spend a lot of time with my kids, and obviously, children and teenagers have a different kind of intelligence. It’s an intelligence more connected to the growth of forms, something linked to nature. It’s also related to a supernatural nature, which I would describe as… I don’t know, something we no longer see or perceive. It’s an intelligence of details, of wonder, of being surprised, of curiosity, of not knowing, of mystery. And obviously, there’s also another kind of intelligence, the animal one. My daughter has a horse, she loves horse riding. She’s thirteen and very dedicated. She competes every week. I’m always worried she might fall, so I try to be there as much as I can.

Sometimes, during the breaks in her competitions, when she’s focused on what she has to do, I have some time alone, and I like to spend it just staring at the horses. Horses are very beautiful creatures, but they have this very long face, which is visually challenging because you can’t exactly tell what they’re thinking or looking at. I like to watch them. Maybe we will find a way to use AI to re-establish or better understand the kind of intelligence animals have; an intelligence related to wildlife, something like a genetic unconscious, let’s call it that. There’s also an intelligence of plants. And definitely, there are some things I always recommend, which is, if possible, to get closer to nature. I think this is possible even in big cities. In all the big cities in Italy, at least in Europe, and probably everywhere, you can find a little park or a small forest where you can go for a walk.

And do some photosynthesis.

A first version of this interview was published in Title(s), I’M Firenze Digest first printed edition, published for TEXT(S)TURE(S), Istituto Marangoni Firenze Fashion Show 2025.